What Austin Bought And Sold In March 2025

This is the next installment in our monthly series on the portfolio of our macro analyst, Austin Rogers. Please note that our main focus will remain on the HYL Portfolios, but since many of you have expressed interest in knowing how Austin manages his portfolio, we are posting this to give you extra value.

This month was another sleepy one for my portfolio in terms of trades, but fortunately, it was the opposite of sleepy in the economic and political environment. So there's still plenty to discuss this month.

I'll start by giving some thoughts on inflation, trade, and tariffs, then I'll turn to my portfolio to discuss where things stand today.

The Global Trade Order Crumbles

Here at High Yield Landlord, we have been making the argument for a year or so now (via our monthly Market Updates on the CPI) that inflation is lower than it appears.

The severely lagging shelter component of the CPI suppressed inflation readings in 2021 and 2022 when real-time inflation was surging, and it is now having the opposite effect as real-time inflation has collapsed.

We have been arguing that the CPI will gradually re-converge with real-time inflation at a lower level, which would prompt the Fed to continue cutting interest rates.

What is missing from this narrative?

Tariffs.

Over the last few months, President Trump has imposed 25% steel and aluminum tariffs as well as 20% tariffs on all Chinese imports and 25% tariffs on all Canadian and Mexican imports not covered by the USMCA. He has promised 25% tariffs on all auto imports as well as "reciprocal tariffs" (whatever that ends up meaning).

You're probably reading this after the April 2nd "Liberation Day" (about as Orwellian a phrase as "Inflation Reduction Act"), so you likely know more than I do as of this writing about the details of the new trade regime. (New update coming soon!)

But in any case, some things are clear.

The first-order effect of tariffs, as has been widely covered in the media, is inflation. Importers will build the cost of the tariffs into their goods prices, and protected domestic producers will be able to raise price as a result of the higher import prices.

But some retailers and businesses in highly competitive industries won't have the market power to raise prices, at least not enough to fully offset the cost of the tariffs. These companies will see their margins permanently reduced.

A second-order effect of tariffs will be that the basket of consumer spending will shift. As some products get more expensive, consumers will have less money for other things. Many services will be hurt as consumers' budgets go more heavily toward goods.

Another second-order effect will be the impact of retaliatory tariffs, which will come. Foreign countries aren't just going to roll over and accept whatever Trump demands. Foreign leaders are going to act in the interest of their economies, just as Trump is acting in (what he believes to be) the interest of the USA.

What will be the third-order effects of the tariffs? I'm not smart enough to know. But the more you think through all the consequences of these trade wars, the clearer it becomes why the vast majority of economists view broad-based tariffs as bad economic policy.

Trump believes he will grow the US manufacturing base and help his rural working class supporters through this policy, but the record of history shows he will instead raise prices for everyone while destroying far more jobs than he creates or protects.

It's useful to remember that the growth of international trade has played a significant role in the disinflationary trend of the last 40 years.

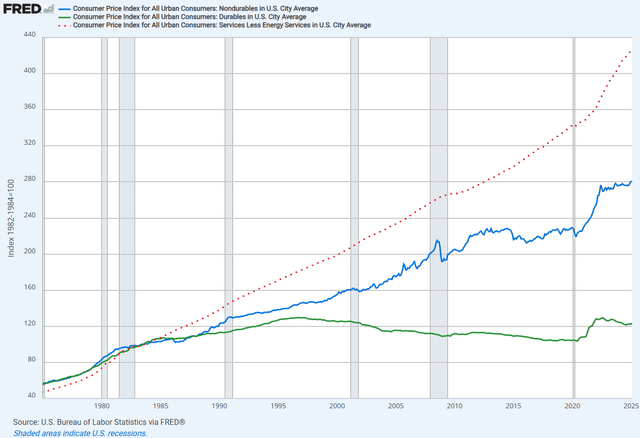

The green line below represents the price index for durable goods (cars, furniture, appliances, etc.). The blue line represents the price index for nondurable goods (food, clothes, electronics, etc.). The dotted red line represents the price index for all services except energy-related services.

Obviously, international trade primarily affects goods, whereas the vast majority of services are domestically produced.

Notice that up through the mid-1980s, goods prices rose just as fast as services.

Then, in the 1980s, President Reagan and Milton Friedman helped to popularize free trade, and a movement began to reduce trade barriers and expand international trade volumes. Imports from Japan grew rapidly in the middle years of the decade. The GATT's Uruguay Round began in 1986 and led to more international trade. The US-Canada Free Trade Agreement went into effect in 1988. NAFTA went into effect in 1994, bringing Mexico into the North American free trade family.

Then, finally, in late 2001, China joined the World Trade Organization (the spiritual successor to GATT), which caused Chinese exports (and imports) to explode higher.

The result for consumers was indisputably a wider variety of goods and lower-than-otherwise prices.

You can see the divergence between goods and services prices beginning in the mid-1980s and steadily widening over time. Durables goods that have more components especially benefited from international supply chains.

This flies in the face of the protectionist narrative that the only thing imported from countries like China and Mexico is "cheap crap" like plastic toys and fast-fashion clothes.

In the past, we have suggested that tariffs cause a one-time price increase -- or "price adjustment," as Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent called it. But how long exactly this price adjustment takes is in question.

Importers with strong pricing power will be able to raise prices immediately. Those with weaker pricing power will raise prices slower, if they can rebuild their margins at all. But if producers actually reshore manufacturing to the US, the process of building new production capacity will take years and cost hundreds of billions of dollars. In that case, price adjustments will still be happening many years from now as producers build the costs of this new US-based manufacturing capacity in to their prices.

As explained in the Wall Street Journal:

By reducing competition, trade barriers allow domestic producers to raise prices more. The gap between U.S. and world steel prices has risen sharply since January because of tariffs, for instance. With less foreign competition, domestic producers feel less pressure to adopt the latest technology or boost worker productivity, adding to cost pressures over the long term.

Without foreign competition (or with severely disadvantaged foreign competition), the default rate of inflation is almost certainly higher.

I don't think that reversing the multi-decade globalization trend can or will be achieved in a year or two. It would likely take decades.

And it would involve untold destruction of wealth and consumer purchasing power.

I highly doubt the next US president will be as cavalier about starting trade wars as the current one, but the question is whether Trump will take his finger off the self-destruct button in the face of bad economic and stock market performance. As of now, the data does not suggest that.

But candidly, I have no idea what Trump will decide to do. I don't think anyone does.

Until greater clarity is obtained, I am not making any meaningful changes to my portfolio. So far, though I think the tariffs will have a significant impact on the economy, I don't think any of my holdings' investment theses are broken because of them.

Q1 2025 Portfolio Dividend Update

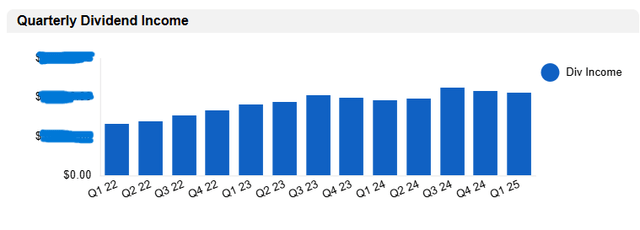

My Q1 2025 portfolio dividend income came in slightly lower than I expected, although this reading is as of March 31st. As usual, dividends/distributions from the Brookfield family (BAM, BIP, and BEP) take an extra day to hit my Vanguard account and don't show up yet despite technically being paid out at the end of the month.

It is disappointing to see the flattish quarter-over-quarter number, but I'm heartened that on a year-over-year basis, Q1 2025 dividends were up 9.4%.

I still expect quarterly dividend growth to return to growth over the course of this year, but it may be a bumpy ride.

One big reason for the coming bumpiness will be Arbor Realty's (ABR) "dividend adjustment" to be announced in a month or so. Normally, a dividend cut would be the ultimate red flag for me, but in ABR's case, I don't think it signifies any poor capital allocation decisions. It's just the unavoidable outcome of the historic surge in interest rates over the last four years. ABR's management team remains the best in the business, and I'm still bullish on the name long-term.

ABR makes up 0.9% of my portfolio by market value but 2.5% of my portfolio's total income.

As a result, Q2's portfolio income may be slightly lower, but I am hoping that dividend growth and investing unspent labor income will make up for this lost dividend income fairly quickly.

Top 10 Holdings

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to High Yield Landlord to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.