MARKET UPDATE - The Five Horsemen Of Disinflation Vs. The Three Plagues Of Inflation

Dear Landlords,

I want to extend a warm welcome to all our new members! We recommend that you start by reading our Welcome Letter by clicking here. It explains why we invest in real estate through REITs and how to get started.

As a reminder, our most recent "Portfolio Review" was shared with the members of High Yield Landlord on January 6th, 2024, and you can read it by clicking here.

You can also access our three portfolios via Google Sheets by clicking here.

New members can start researching positions marked as Strong Buy and Buy while taking into account the corresponding risk ratings.

If you have any questions or need assistance, please let us know.

==============================

MARKET UPDATE - The Five Horsemen Of Disinflation Vs. The Three Plagues Of Inflation

In the Biblical book of Revelation, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse represent war, famine, pestilence, and death.

And in the Biblical book of Exodus, 10 plagues were sent by God upon the people of Egypt as a means of pressuring the Pharaoh to free the Israelites from enslavement.

Alright, now that you understand the references, forget all about their original intended meaning.

For the sake of this article, the "horsemen" are not necessarily negative, and the "plagues" are not necessarily sent by God. They are just illustrative concepts.

We have written in the past about what we call the "Five Horsemen of Disinflation."

These Five Horsemen are:

Aging Demographics: Aging populations and falling birth rates put downward pressure on economic, labor force, and consumer price growth.

Technology: Productivity-enhancing technological advancements are inherently labor-saving and disinflationary/deflationary.

Over-Indebtedness: Debt levels above certain thresholds have been demonstrated by numerous academic studies to weigh down economic growth and suppress inflation.

Globalization: International trade puts downward pressure on net importer nations' inflation and wage growth.

Inequality: A smaller portion of money in the pockets of those with a higher propensity to spend translates into lower-than-otherwise aggregate demand.

We would assert that each of these Five Horsemen remain alive and well -- and continue to gallop, if you will.

While we have admittedly been too early in past calls that these Five Horsemen are reasserting themselves and exerting strongly downward pressure on inflation, we believe they remain in place and unlikely to be disrupted.

However, the global economy is complex, and these are not the only forces at play within it.

In the past, we have probably been guilty of focusing too heavily on the Five Horsemen at the expense of other forces that are working in opposite directions.

Specifically, we need to grapple with what might be called the "Three Plagues of Inflation."

These Three Plagues are:

Excessive Fiscal Stimulus: As demonstrated during and after COVID-19, excessive fiscal stimulus, especially when aimed at increasing consumption without a simultaneous increase in supply and/or productivity, is highly inflationary.

Disruptive Trade Barriers: Political barriers to international trade decrease overall economic efficiency and raise costs for net importer nations, such as the US.

War: Nothing disrupts global trade or leads to greater spending on economically unproductive (even if geopolitically necessary) uses than large-scale wars.

While there certainly could be other "plagues," or causes, of inflation, we think these three pose the biggest threat to the world in the current environment.

Which will win over the other in the near-, intermediate-, and long-term periods?

Some believe that the post-Great Financial Crisis era of the 2010s was uniquely disinflationary and marked the lowest point in inflation and interest rates that we will see in our lifetimes. And to be certain, there were some absurdities from that era, such as nearly $20 trillion in global negative-yielding debt, that the world may never see again.

But has the era of low inflation, low interest rates, and low economic growth come and gone?

Have we entered a new era of mega-growth courtesy of artificial intelligence as well as elevated inflation and interest rates courtesy of the Three Plagues of Inflation?

You won't be surprised to hear that we aren't in possession of a crystal ball. But while it is very difficult to make predictions (especially about the future!), here is our broad macro outlook:

The Three Plagues may cause temporary periods of inflation in the future, but the overall trajectory remains toward a prolonged environment of low inflation, low growth, and low interest rates, due to the Five Horsemen.

Below, we explain the thinking behind this macro outlook.

The Three Plagues of Inflation

If you think about it, the natural state of a free enterprise system operating within a society characterized by the rule of law would be one of low inflation or even mild deflation.

Over time, competitive actors in the market would figure out how to extract resources from the earth at greater efficiency and scale. Other competitive actors then turn these resources into attractive products at as low of prices as they can while turning a profit. For every boom in demand, there is a boom in supply.

Elevated levels of inflation signify that something is going wrong in the economy. There is some mismatch between the natural functioning of supply or demand, or both.

The Three Plagues of Inflation are three such ways that the smooth functioning of the economy can be disturbed and distorted.

Excessive Fiscal Stimulus

The US government's response to the COVID-19 pandemic is a perfect example of how excess fiscal stimulus creates inflation.

In order to avert a deep recession (which is usually the justification for excessive fiscal stimulus), the government engaged in unprecedently massive, direct-to-consumer fiscal stimulus. This took multiple forms, from "economic impact payments" (aka "stimmy checks"), forgivable business loans to keep idle workers employed, extra unemployment benefits, and so on.

The result was an absolute tidal wave of money flooding into the economy, virtually all at once.

At one point, the year-over-year growth in the money supply reached 25%.

This naturally resulted in a situation in which too much money was chasing too few goods.

There is a lot of confusion about what exactly caused the wave of inflation that followed this wave of money, but make no mistake: The original sin was excessive fiscal stimulus.

Some people blame the Federal Reserve for effectively monetizing the Treasury Department's debt issuance to pay for this fiscal stimulus. The Fed purchased virtually all debt issued by the Treasury Department during the period of stimulus spending.

But regardless of how it is financed, putting trillions of dollars into the pockets of consumers is bound to produce inflation. If the Fed had not monetized the debt issued to perform this stimulus, Treasury yields likely would have shot up as a function of supply and demand. But assuming the Treasury Department would have been able to issue sufficient debt, even at high yields, to pay for the fiscal stimulus, there would still have been inflation.

Some people also believe that the core problem wasn't the fiscal stimulus but rather the lack of supply on the market at the time.

Exactly as Americans were cash-rich from fiscal stimulus, large swathes of the services economy were unavailable due to social distancing, and large segments of the goods side of the economy were experiencing labor shortages, downtime, production delays, supply chain kinks, and so on.

Undoubtedly, supply breakdowns played a significant role in the inflationary surge of 2021-2022.

But the original sin -- the primary cause of inflation -- was excessive fiscal stimulus.

If not for the fiscal stimulus, supply would have collapsed, but consumer demand would have collapsed as well.

With a sizable minority of the population not working and the savings rate shooting up among those who were working, aggregate demand would have gapped far lower during the pandemic -- if not for the stimulus.

Of course, the argument of the stimulus defenders is that some people would have been destitute if not for the government's assistance, and the economy would have plunged into a depression.

This is where the word "excessive" comes into play.

In theory, there is some optimal level of fiscal stimulus that acts as a true safety net for those most impacted while stopping short of largesse for everyone else who does not. The COVID-era stimulus was not that. It dramatically overshot the amount of assistance required to avoid destitution and depression.

We know that is the case because of the incredible inflationary boom experienced in its aftermath.

In future recessions or shocks, excessive fiscal responses certainly do have the capacity to create significant, if temporary, bouts of inflation.

Disruptive Trade Barriers

Of the various aspects of the globally interconnected economy, supply chains are among the most complex.

Over decades, multi-country supply chains have been steady established like animal trails in the forest or neural grooves in the brain. For any given final product, raw materials and intermediate parts tend to come from multiple countries around the world.

In the decades after the ratification of NAFTA, automobiles typically cross back and forth across the border several times (up to 8 times, in some cases), as a component is added here and another component added there.

That's just how supply chains developed over time as managers sought to optimize.

So what happens when politicians raise trade barriers in order to protect domestic producers and/or substitute imports for domestically produced goods?

Overwhelmingly, the result is less efficiency and higher costs.

The erosion of efficiency comes largely from the sudden reworking of supply chains that have been slowly and steadily pieced together over the course of years or decades. Often, there is no domestic producer of a certain good subject to trade barriers. Other times, a foreign producer in a country without trade barriers can make the good but at lower quality or higher cost.

But another source of inefficiency comes from the legal and bureaucratic angle. Many businesses find it more worthwhile to fight the tariffs through legal or bureaucratic channels rather than simply pay them or find ways to avoid them.

After the broad-based Section 301 tariffs were placed on China in 2018-2019, a tsunami of exclusion requests poured in from across the economy, most of which were rejected.

Spending hundreds of millions or billions of dollars on lobbying instead of one's actual business is a recipe for greater system-wide inefficiency.

All of the above results in increased inflation for the impacted goods.

In 2023, the US International Trade Commission released a study finding that consumers ultimately paid for virtually the entire cost of the 2018-2019 tariffs, while domestic producers of the impacted goods saw very little benefit.

More recently, the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office performed an analysis of the incoming president's proposed tariff proposals. They found that a 10% universal tariff combined with a 50% tariff on all imports from China would result in an increase of 1% to the PCE index (not including the effect of retaliatory tariffs).

Another analysis by the Peterson Institute for International Economics, however, shows a much higher inflationary impact from Trump's various economic policies, most notably tariffs:

Notice, however, that even in PIIE's worst-case scenario, which we find unlikely, the inflationary shock would only persist for a few years before reverting back to a 2% baseline.

Here, again, we find that the second Plague of Inflation threatens nothing more than a temporary burst of inflation, not a change in the long-term secular trajectory.

War

It should be rather obvious how large-scale wars cause at least temporary bouts of inflation. The mechanisms by which war breeds inflation are a combination of the two other Plagues discussed above.

First, the affected countries (and others that are afraid of being dragged into the conflict) must spend more money on economically unproductive goods and endeavors. Of course, some worthy endeavors do not have an economic ROI and need to be done anyway, for geopolitical or other reasons. But that doesn't make wartime spending economically productive.

Famous economist John Maynard Keynes taught that in order to stimulate the economy, governments just need to spend -- on anything. Hire people to dig ditches (a common assignment for soldiers) and then refill them. It doesn't matter if the labor is productive or not.

But this sounds foolish in light of the experience of COVID-19. People were paid to do nothing productive during that crisis, and it contributed mightily to inflation.

Moreover, war causes a greater share of a nation's resources to go toward military uses, which results in more shortages in the private economy. This, too, contributes to inflation.

Second, war results in sudden cutoffs in trade between certain countries.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is the perfect example, as Western Europe decided to rapidly wean itself off Russian oil & gas in the aftermath.

While this resulted in a sharp drop in the price of Russian oil & gas, few nations across the world were willing to buy it.

That caused the rest of the world's oil & gas to immediately shoot up in price:

But, again, notice that the hugely disruptive and rapid shift away from Russian fossil fuels and toward other suppliers caused only a temporary bounce in prices.

Likewise, Ukraine is a major producer of wheat (represented by the gold bar in its flag), and the spread of military conflict across its wheat fields, as well as the Russian embargo of Ukraine's seaports, caused a pronounced -- yet temporary -- spike in global food prices:

But, as for the cutoff of Russian oil & gas, the disruption to Ukraine's wheat supply caused only a transitory burst of inflation.

By its nature, war is a temporary phenomenon.

The inflationary impacts of war are likewise temporary.

The Five Horsemen Are Still Charging Forward

The primary difference between the Five Horsemen and the Three Plagues is that the latter are temporary and the former are permanent.

The Plagues cause short-term (although it can feel long-term in the moment!) inflationary effects.

But the Horsemen are permanent forces in the economy exerting downward pressure on inflation.

Aging Demographics

Take aging demographics, an inescapable reality for all developed nations on Earth.

As the population ages and a greater share of the population enters retirement, downward pressure on aggregate demand grows. Research from the RAND Corporation shows that spending declines consistently after age 65, regardless of wealth, gender, marital status, employment status, or virtually any other factor. And a multitude of studies have found that spending drops significantly after a worker retires.

Over the course of one's lifespan, spending forms a bell curve, peaking in midlife (40-60 years old) and declining thereafter.

It makes sense.

Midlife is the age when kids are most expensive. They need clothes, cars, college tuition, and so on. It's also the age when people are peaking in their careers, taking the most vacations, buying bigger homes, and showing off fancy new cars.

Now consider also that the affluent are retiring earlier than they used to, as illustrated by the labor force participation rate for the age 55+ group:

Extrapolate these points out to the entire population of the United States, and in fact the entire population of the developed world.

As a greater and greater share of the population enters retirement and old age, this will exert downward pressure on aggregate consumption, which in turn exerts downward pressure on inflation.

Outside of the temporary shocks of COVID and the war in Ukraine, this is the pattern we've seen in Japan, the Eurozone, the UK, Canada, and, yes, also here in the United States.

Technology

Think also about the ways in which technological advancements improve productivity and reduce business costs, the savings of which can then be passed on to consumers.

Artificial intelligence holds great promise in bringing about a huge increase in such productivity in the near term.

For example, a 2023 study by MIT researchers found that AI programs can make high-skilled workers up to 40% more productive at their daily tasks.

Goldman Sachs concurs with research showing "very positive signs" that AI will eventually boost productivity and GDP growth.

In some cases, this AI-driven productivity boom has likely already begun, but like the Internet, it will take a very long time to be fully integrated into the economy.

This productivity boom will likely result in a gradual decrease in demand for labor in certain areas of the economy. It should also increase the efficiency of production in various other ways, which reduces producer costs and ultimately results in downward pressure on consumer prices.

Over-Indebtedness

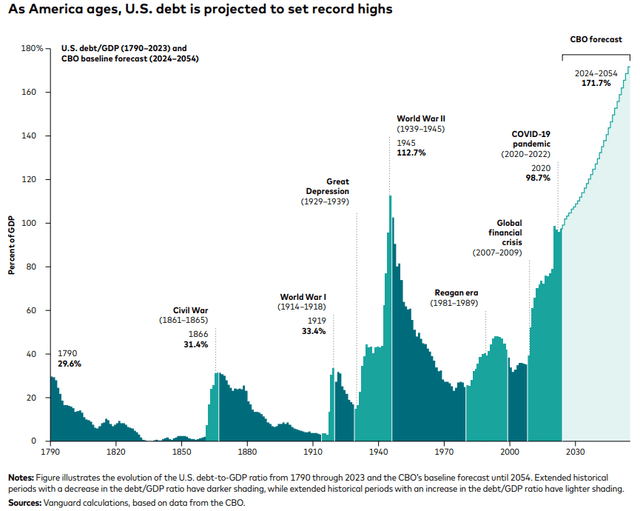

While it remains a topic of debate in the field of economics, the majority of studies find that there is a threshold of government debt to GDP that, when exceeded, begins to increasingly weigh down economic growth.

That threshold is anywhere from 60% to 110% debt to GDP, but the most commonly found threshold is 90%.

For the US, that 90% threshold was passed in the early 2010s. The highest threshold generally found by the studies of 110% was passed when COVID-19 struck.

You might argue that it is better to use debt held by the public instead of total debt, which includes that which is held by government agencies or trust funds.

Federal debt held by the public jumped from about 80% of GDP before COVID up to the mid-90% territory after COVID, where it hovers today.

Given the trajectory of US fiscal deficit spending, that number is likely only going higher.

If the economic research holds true for the US, then, the level of government debt should exert downward pressure on both economic growth and inflation going forward.

Globalization

While there is a lot of talk about trade barriers and anti-globalization efforts, it is important to remember that demand for international trade remains overwhelmingly strong across the world.

After a down year in 2023, global trade volume is estimated to have rebounded to a new record high of $33 trillion in 2024.

Cross-border services growth remains robust at 7% in 2024, but cross-border trade in goods also grew again last year.

Despite trade barriers being raised by governments across the world, the private sector continues finding ways to maintain trade flows. It is simply far more efficient for businesses to source goods internationally in many cases than it is to rely on domestic industry.

And the pandemic-era supply chain kinks that greatly disrupted trade have now smoothed out:

Demand for freight container shipping hit an all-time high for the first five months of 2024, as the volume of containers shipped rose even past its post-COVID highs.

And we here in the United States are not being left out of the growth in global trade, despite the rising political popularity of protectionism.

Both imports and exports of goods were just below their all-time highs (set during the post-COVID boom) at the end of Q3 2024:

While international trade is losing popularity with average Americans, according to a recent Pew Research survey, businesses and people continue to vote with their wallets for more international trade.

Moreover, as articulated by research put out by Vanguard, slowing globalization, or "slowbalization," may not necessarily translate into higher inflation.

While globalized trade flows have contributed to lower-than-otherwise inflation, the impact has not been that significant -- never more than 1% at any given time, and usually closer to 0.25% to 0.5%.

That is, overall inflation with globalization is usually only 0.25-0.5% lower than it would be without globalization.

This is not because globalization doesn't lower the costs of impacted goods. It does.

Rather, it is because the US economy is overwhelmingly services-based, and it is getting even more so over time.

Large trade barriers and high tariffs would raise inflation by some degree, whether it is the 1% estimated by the CBO or the 4-7% estimated by the Peterson Institute.

But the effect would be temporary, and its effect could very well be offset by disinflation or deflation in other, larger areas of the economy like services.

Inequality

Finally, consider the level of economic inequality extant in the US and its impact on inflation.

We are not trying to make any political point or advocate for any political policies by discussing this (although we use charts put out by the Left-leaning Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, which certainly do advocate for certain policies).

Instead, we are simply observing and deducing effects.

By one measurement (others show slightly different outcomes), the highest earners in the 95th percentile have enjoyed dramatically faster real income growth than the median earner over the last 20- and 40-year periods.

Some ways of measuring real income growth find that the highest earners have not done quite as well as the chart above depicts, but virtually all measurements show the top performing much better than the median or lower-income groups.

And, of course, in an era of mega-cap companies and a growing number of billionaires, it shouldn't be surprising that wealth disparities are massive:

Given that the CBPP uses data from government sources like the Fed, we believe it can more or less be trusted.

The post-COVID inflationary surge probably contributed to increased inequality, because lower-income groups spend a larger share of their income and save little to nothing. Plus, because of a phenomenon called "cheapflation" in which cheaper goods tended to see disproportionately high price hikes, the real impact of inflation has had a disproportionately negative impact on the lowest income households.

However, while there is very little research on this topic, we believe that higher inequality puts downward pressure on inflation, because it means that a greater proportion of income and wealth are concentrated in households with a lower propensity to spend.

As the economic paths of the Affluent and the Paycheck-to-Paycheck population continue to diverge, we think this puts downward pressure on inflation as a whole.

Bottom Line

As we have discussed in the past, inflation and elevated long-term interest rates are a strong headwind to REIT price performance.

Since REITs are largely correlated to bonds, and bonds perform poorly when inflation and interest rates go up, higher inflation and interest rates are the enemy of REITs as well.

That is why we believe our macro outlook for inflation (and eventually long-term interest rates) to remain low for the foreseeable future, unless one of the Plagues shows up, is great news for REITs.

In fact, for the last year and a half, inflation using real-time housing data has already been very low:

We believe real-time inflation will continue to hover at very low levels, and the CPI will eventually rejoin it at those low levels.

This outlook is corroborated by forward inflation expectations. For both the one-year and three-year ahead periods, inflation expectations are no higher today than they were before COVID-19.

We believe the preponderance of evidence points to these expectations being correct, putting aside the distinct possibility of inflationary yet temporary outcomes from Trump's policies over the next few years.

Put simply, we believe the Five Horsemen have collectively put the economy on an unstoppable secular trajectory toward low inflation and low interest rates. Low inflation will come first, and interest rates will follow.

Of course, any of the three Plagues (or multiple acting in unison) could temporarily disrupt that.

In fact, we think COVID-19 is an example of such a temporary, if sharp and painful, disruption to that overall trajectory.

But short of a short-term inflationary surge from excessive fiscal stimulus, significant trade barriers, and/or war, we believe the US economy will return to a state of low inflation and ultimately low interest rates as well.

That is the ideal environment for REITs to thrive.

Finally, please note that we exceptionally posted this article without a paywall. If you found it valuable, consider joining High Yield Landlord for a 2-week free trial to access the rest of this series.

You will also gain immediate access to my entire REIT portfolio, real-time trade alerts, exclusive REIT CEO interviews, and much more. We are the largest and highest-rated REIT investment newsletter online, with over 2,000 paid members and more than 500 five-star reviews.

We spend 1000s of hours and over $100,000 per year researching the market for the most profitable investment opportunities and share the results with you at a tiny fraction of the cost.

Get started today - the first 2 weeks are on us:

Analyst's Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of all companies held in the CORE PORTFOLIO, RETIREMENT PORTFOLIO, and INTERNATIONAL PORTFOLIO either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. High Yield Landlord® ('HYL') is managed by Leonberg Research, a subsidiary of Leonberg Capital. All rights are reserved. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. The newsletter is impersonal and subscribers/readers should not make any investment decision without conducting their own due diligence, and consulting their financial advisor about their specific situation. The information is obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The opinions expressed are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. We are a team of five analysts, each contributing distinct perspectives. Nonetheless, Jussi Askola, the leader of the service, is responsible for making the final investment decisions and overseeing the portfolio. We do not always agree with each other and an investment by Jussi should not be taken as an endorsement by other authors. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Our portfolio performance data is provided by Interactive Brokers and believed to be accurate but its accuracy has not been audited and cannot be guaranteed. Our portfolio may not be perfectly comparable to the relevant index. It is more concentrated and may at times use margin and/or invest in companies that are not typically included in REIT indexes. Finally, High Yield Landlord is not a licensed securities dealer, broker, US investment adviser, or investment bank. We simply share research on the REIT sector.